Post-9/11 Afghan Democracy: Far More Distant than Expected

Disillusioned population losing faith in NATO

Reading time: (Number of words: )

All the versions of this article: [English] [فارسى]

This article aims to evaluate the post-9/11 efforts of the international community and the government of Afghanistan towards institutionalizing democracy in Afghanistan. Not only the efforts of the international community and the Afghan government has been critically analyzed in this article, but also the positional factors such as counter-warlordism and counter-insurgency that have significantly undermined the post-2001 Afghan democratization process have been evaluated.

In the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, the UN-sponsored Bonn Conference of 2001 not only intended to build sustainable peace in Afghanistan but also opened the window for a formal democratization process in the post-Taliban era. The Bonn Conference resulted in the Bonn Agreement of 5 December 2001 that recognized the right of the people of Afghanistan to freely decide about their political future with reference to the principles of Islam, democracy, pluralism, and social justice. Regardless of the formal recognition of democracy by the Bonn Agreement, in the post-2001 period, both the Afghan government and the international community paid less attention in providing the ground for institutionalizing democracy in Afghanistan due to the ongoing challenges of warlordism and the Taliban-led insurgency.

As a result of shifting the attention of the international community and the Afghan government from democracy to counter-warlordism and counter-insurgency, democracy has neither institutionalized nor systematically developed across permanent institutions in post-9/11 Afghanistan.

To begin, the Bonn Conference in its own did not provide the ground for the democratization of Afghanistan. While the Bonn Agreement of 2001 recognized the right of the people of Afghanistan to freely decide about their political future, it did not practically provide the Afghan people with the opportunity to democratically decide about the future of their country. Ironically, the participants in the Bonn Conference were the representatives of Afghan opposing groups that were neither democratically elected by the people of Afghanistan nor had legitimacy among various Afghan ethnic groups especially Pashtuns, Tajiks, Hazaras, and Uzbeks.

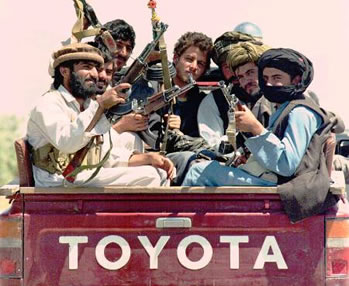

Such a non-democratic mechanism paved the way for the representatives of Afghan competing groups particularly warlords to entirely dominate the political power in post-9/11 Afghanistan. As a result, the internationally-sponsored Bonn Conference of 2001 deliberately provided each Afghan opposing group with a share of power in the political administration of post-Taliban Afghanistan; however, neither the international organizers of the Bonn Conference nor Afghan participating groups took democracy and the democratic right of the people of Afghanistan as an issue of central importance.

In addition to the Bonn Conference that non-democratically provided warlords with the exceptional opportunity to dominate political power in Afghanistan, during the implementation of the Bonn Agreement between the years 2001 and 2006 the dominance of warlords over permanent political institutions undisputedly continued.

Despite the fact that during the Bonn Process the international community consistently attempted to decrease the power of warlords over national institutions, such efforts did not necessarily contributed to the end of warlordism and the success of democratization process in Afghanistan. Paradoxically, the international community entirely focused on counter-warlordism as the main obstacle towards democratization process rather than investing in institution-building process for the development of Afghan democracy. Not only the international community but also the government of Afghanistan in the course of the implementation of the Bonn Agreement was partly unsuccessful in building permanent institutions for the intention of institutionalizing democracy in Afghanistan.

As a result of over-concentration of both the international community and the Afghan government on counter-warlordism, Afghan democracy never found the opportunity to be institutionalized between the years 2001 and 2006.

For instance, although the Presidential and Parliamentary elections of 2004 and 2005 were two significant steps towards institutionalizing democracy in post-Taliban Afghanistan, the internationally-backed government of Afghanistan was unable to counter the challenge of warlordism during and after the elections. Thus, not only the elected government of President Hamid Karzai but also the Parliament of 2005 as well as the Afghan Judiciary significantly remained under the dominance of warlords especially whom they had strong political ties with the government of President Karzai. As a result of the failure of the government of Afghanistan and the international community in effectively dealing with the challenge of warlordism during the Bonn Process, the efforts of the international community did not necessarily resulted in institutionalizing democracy in Afghanistan.

Finally, in the post-Bonn Process, the emergence of the Taliban-led insurgency has shifted the attention of the international community and the Afghan government from institutionalizing democracy to counter-insurgency. Once the Taliban and other insurgent groups became able to increase the insurgency after 2003, not only the international community but also the government of Afghanistan saw democracy as an issue of less important in comparison to the priorities of counter-insurgency. Institutionalizing democracy and building sustainable democratic institutions in the post-Bonn process, therefore, have not only disappeared from the policy priorities of the international community but also the Afghan government has entirely forgotten its national responsibility in strengthening democracy.

Regardless of the attempts of the international community in supporting the democratization process in the post-Bonn Process, the government of Afghanistan has paid no significant attention to the democratization process of the country. The Afghan government has not only less focused on institutionalizing democracy, but also continuously restricted democratic freedoms of citizens due to the increase of security concerned posed by the Taliban and other insurgent groups.

For example, the fraud-tarnished Presidential and Parliamentary elections of 2009 and 2010 have been two obvious examples of democratic deficit in the post-Bonn Process in Afghanistan. In these two elections, the transparency, credibility and inclusivity of the electoral processes were significantly undermined by the widespread fraud and corruption across the country. While in the post-Bonn Process the focus of the international community has shifted from the priority of the democratization of Afghanistan to counter-insurgency, the Afghan government has been over-confident in paying no attention to democracy. As a result, while the international community has failed to oblige the Afghan government in convening transparent and credible elections in 2009 and 2010 to further building democratic institutions, Afghan democracy is seemingly far longer from the expectations of the people of Afghanistan as well as the international community.

To conclude, both the international community and the government of Afghanistan have failed to institutionalize democracy in the post-2001 era. Despite few democratic achievements at the primary stages of the Bonn Process, the Afghan democratization process has neither been successful nor found the ground for systematically development in post-Taliban Afghanistan. The reason behind the failure of the democratization process in post-9/11 Afghanistan has not only been the over-concentration of the international community on counter-warlordism and counter-insurgency, but also the failure of the internationally-backed Afghan government in effectively dealing with such challenges has further undermined the democratization process. To better strengthen democracy, it is important for the international community to oblige the Afghan government in systematically institutionalizing democracy and building sustainable democratic institutions; otherwise, the challenges of warlordism and the Taliban-led insurgency would more undermine the democratization process to further result in the entire failure of Afghan democracy.

Farhad Arian is a former official of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Afghanistan. He is currently undertaking a Master of Arts in International Affairs at the Australian National University (ANU).

References

Afghanistan, (2010), The New York Times. Retrieved November 23, 2010 from www.topics.nytimes.com.

Afsah, E. & Guhr, A. H. (2005), “Afghanistan: Building a State to Keep the Peace”, Bogdandy, A. V. and Wolfrum, R. (eds.), Max Planck Yearbook of United Nations Law, V. 9, pp. 373-456.

Enterline, A. J. & Greig, J. M. (2008), “Against All Odds? The History of Imposed Democracy and the Future of Iraq and Afghanistan”, University of North Texas, Department of Political Science, pp. 1-52. Retrieved November 10, 2010 from www.psci.unt.edu.

Jalali, A. A. (2006), “The Future of Afghanistan”, Parameters, pp. 4-19. Retrieved November 15, 2010 from www.carlisle.army.mil.

Johnson, T. (2006), “Afghanistan’s post-Taliban Transition: The State of State-Building After War”, Central Asian Survey , Vol. 25, No. 1-2, pp. 1-26.

Hartzell, C. & Hoddie, M. (2003), “Institutionalizing Peace: Power Sharing and Post-Civil War Conflict Management”, American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 47, No. 2, pp. 318-332.

Matisonn, J. (2010), “How the West Failed Afghan Democracy?”, Financial Times. Retrieved December 3, 2010 from www.ft.com.

Owen, A. (2009), “A Third Way: The Best Strategy in Afghanistan is neither Complete Withdrawal nor More Troops”, Progress Online. Retrieved December 1, 2010 from www.progressonline.org.uk.

Suhrke, A. (2007), “Democratization of a Dependent State: The Case of Afghanistan”, Working Papers, Chr. Michelsen Institute, pp.1-15. Retrieved November 15, 2010 from www.journalsonline.tandf.co.uk.

The Future of Democracy in Afghanistan, (2009), The Government Monitor. Retrieved November 24, 2010 from www.thegovmonitor.com.

Wollman, N. & Hairan, A. (2010), “Do We Want a Stable Democracy in Afghanistan or Just a Short Term Ally to Fight the Taliban?”, PSYSR Blog. Retrieved December 2, 2010 from www.psysr.wordpress.com.

Poems for the Hazara

The Anthology of 125 Internationally Recognized Poets From 68 Countries Dedicated to the Hazara

Order Now