The Bookseller of Kabul Replies to Åsne Seierstad

Popular bestseller called "cock and bull story"

Reading time: (Number of words: )

by Farooq Sulehria

(editorial assistance by Shane Tasker)

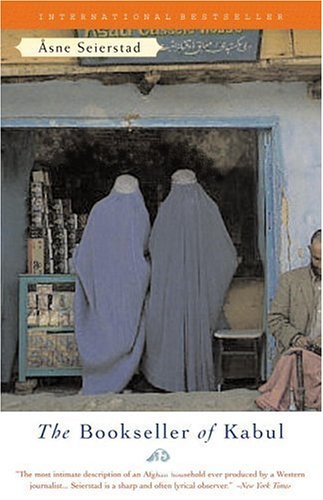

Of late, I have developed a hatred for "bestsellers." These books often prove to be a waste of time. A bestseller becomes a particularly irritating imposition on one’s time when it achieves "controversial" status. The Bookseller of Kabul by Åsne Seierstad was no exception when it began making headlines three years ago.

I read it when it had become both controversial and a bestseller. I simply hated the book. Seierstad, invoking all the Western prejudices about Afghan society and blending them with sensationalism, had tried to delineate the dirty US occupation of Afghanistan as the "white man’s burden," which the West should not shed.

This is not to say that the propaganda commissars at Langley commissioned Seierstad to deliver a sensational book about Afghanistan that an audience in the West would find easy to lap up. However, it was a fantastic coincidence that while President George W. Bush and his wife Laura were telling the West that Afghan women deserved pity, Seierstad was penning these lines: "I have never been as angry as I was with the Khan family, and I have rarely quarreled as much as I did there. Nor have I had the urge to hit anyone as much as I did there. The same thing was continually provoking me: the manner in which men treated women."

Honestly, I have never been as angry as I was after reading Seierstad’s book. Nor have I had the urge to hit anyone as much as I did. What provoked me was the manner in which this quasi-fascist journalist distorted facts and showed disrespect to a culture and country such as Afghanistan.

While lamenting the treatment of Afghan women, Seierstad hero-worshipped a brutal warlord, Ahmed Shah Masood, who was responsible for countless killings and rapes: "He was charismatic, deeply religious, but also pro-western. He spoke French and wanted to modernize the country." The communists, however, were made out to be villains even though the "communist dictators" proved the best rulers for women’s rights.

Similarly, the Taliban were demonized: "Before the Taliban withdrew they poisoned wells and blew up water pipes and dams." (Seierstad could have added that the Taliban were merely following the manuals the US provided to the Afghans who were battling the Soviets in the 1980s.)

As for the mujahideen, there was not a word about how they reduced Kabul to ashes after Dr. Naguib [Najibullah] quit the government.

Seierstad might have punished her poor readers with more bestsellers (she has authored two more books but none have sold as well as the one under discussion here) and become the leading Norwegian Orientalist had "Sultan Khan" (as the bookseller Shah Muhammad Rais was called in Seierstad’s book) and Afghan society been as savage as she portrayed them. Instead of seeking revenge and the issuing of a fatwa against Seierstad, Rais decided to reply to her book with his own book, Once Upon a Time There Was a Bookseller in Kabul. He did so mainly because Seierstad’s book had made his once happy family "deeply unhappy."

"My wife’s brother was the first person to become a victim of Åsne Seierstad’s book," Rais recounts. "The father of one of his classmates read the book and retold parts of it to his son. His son immediately realized that one of his classmates — that is, my brother-in-law — was a relative of the book’s protagonist. This is where the problem started. Soon all my brother-in-law’s classmates were told that his father sold his sister to the bookseller to buy two affordable women for him and his brother, and that the bookseller bribed him and his father so that he could spend the night with his sister before they were married. He was hurt by all this and it led to fights and brawls between him and his classmates."

Rais’ book, though perhaps ghost written, is strikingly impressive in its style. Rais narrates his story to a couple of old trolls sent by the king and queen of trolls who lord over a troll kingdom in northern Norway. At 100 pages it’s a quick read but contains all the elements of a saga: trolls, tragedy, love, hate, revenge and a happy ending.

One by one, Rais not only exposes what he calls Seierstad’s lies but also attempts to enlighten his reader as to the history and culture of Afghanistan. But the book is at heart an attempt to contradict Seierstad’s story.

"There were eight women in the house when Åsne Seierstad came to live with us: my mother, my sisters, my two wives, my two widowed cousins and Najiba, a Hazara woman who worked as a house maid," Rais writes. "Several times during her stay, Åsne Seierstad visited Najiba’s house, and that is where she learned about the difficult situation Afghani women are in."

Rais suspects that any mention of Najiba was carefully avoided in Seierstad’s book so the concocted story about "Leila" would not look meaningless. The story about Leila’s misery is pure invention, he says. Yes, Leila’s education suffered under the Taliban but so did the education of all his children. As soon as the situation improved, however, Leila and his children were back in school.

Rais tells us how Seierstad manipulates the facts in order to concoct a juicy story. One example is in the anecdote about the school curriculum. At one point, Seierstad lists the questions "Fazal" had to answer in his classroom: Can God die? Can God talk? And so on. But what she does not say is that these were from a Taliban-era textbook that was taken out of the curriculum before Seierstad even came to Kabul. "A liar suffers bad memory," Rais says.

"Seierstad makes fun of the union between people and puts price tags on women as if they were cattle," Rais believes. "She even sets their value low."

Contradicting yet another cock-and-bull story of Seierstad’s, Rais tells us: "When my sister got married she was twenty years of age, I was eighteen. Åsne Seierstad claims in her book that my parents sold my sister for 300 pounds to be able to pay for ’Sultan Khan’s’ education. But there has always been free education in Afghanistan!"

Although Rais’s book is worth reading, even better, retrospectively, is an e-mail Rais received from Seierstad on Aug. 20, 2003:

Dear Shah,

As you know, everything in the book is true. But if you prefer to call some things inventions, it’s up to you. That is why I changed your name. So that you are able to say: This is not me, this is maybe based on me, but there are lots of inventions.

I will be very sorry and upset if you mean any of the writing is dangerous for you. What in particular do you mean?

In the time being, in order not to be in trouble, you might say what you just wrote, that these are inventions, that the journalist was here for a few months, she didn’t understand the Afghan way of life, she believed all the stories she heard. This is entirely up to you.

I really don’t know what you are upset about, so please tell me. I am sorry if I put you in any kind of inconvenience. But remember, true stories, true biographies, have both good and bad in them. No person is either good or bad, we are all a mixture, so am I, so are you. The stories from Afghanistan are harsh. The violent past and present do inflict upon people’s lives. This also colors your family’s life.

But again, if the book is a problem for you, please just tell everybody that everything is invented and untrue. I would rather that, then seeing you in trouble. I am sorry if I have disappointed you.

Sincerely,

Åsne

Well, dear Åsne Seierstad, the bookseller has done exactly what you bade him to do. He is now telling "everybody that everything is invented and untrue."

Poems for the Hazara

The Anthology of 125 Internationally Recognized Poets From 68 Countries Dedicated to the Hazara

Order Now